sorry to do this, but for those who care, i gotta let you in on a new book coming out soon...

sorry to do this, but for those who care, i gotta let you in on a new book coming out soon..."I, Little Slave"-- maybe i can make it down in january to hear him read from the book... and i can give you more details. for now though this is all i know:

(edited from the columbian, article by tricia jones)

On a good day, Bounsang Khamkeo could collect rainwater to splash on his face. On a very good day, his makeshift trap would snare a rat, and Khamkeo could enjoy meat for supper.

Such days were few in prison. More frequently, the hours in the jungle "re-education camp" were marked by suffering, abuse and sickness.

Many died in camp, or went insane. Khamkeo refused to do either. He survived seven years of confinement, returned to his waiting family and escaped his native Laos to start a new life in the United States.

Now a Vancouver resident, Khamkeo has written a book he believes to be the first of its kind, detailing the persecution he says he and others

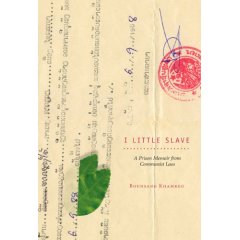

endured under the rule of Laos' Pathet Lao party. "I Little Slave: A Prison Memoir From Communist Laos" (Eastern Washington University Press, $21.95) was released in November.

endured under the rule of Laos' Pathet Lao party. "I Little Slave: A Prison Memoir From Communist Laos" (Eastern Washington University Press, $21.95) was released in November.Its pages chronicle the chaos and corruption accompanying the country's political revolution in 1975. Khamkeo writes of his arrest in 1981, and his life in two filthy jail camps that were notorious for mistreatment.

They were also regarded as deathtraps. Khamkeo said he entered the camps knowing that the Laotian government claimed to be above mistakes. Most prisoners therefore faced life sentences.

"So I told myself, 'If they want me to die in prison, I don't want to die,'" recalled Khamkeo, 66, whose family owns Vancouver's Royal Cuisine restaurant. "'The date I get out of prison, that date I will be the winner.'"

Despite its accounts of physical and mental persecution, Khamkeo's is not a venomous book. It's true that his forthright sentences contain some anger, and occasional profanities. But Khamkeo's deepest wish clearly is for justice for his country, and not personal vengeance.

His message is effective because Khamkeo is not a whiner, says Ivar Nelson, director of the Spokane-based Eastern Washington University Press. Nelson said "I Little Slave" transcends its setting. It could come from Chechnya or Guatemala or an Iraqi prison, he said.

"It's a human story of perseverance through incredible difficulties and maltreatment ... and (ultimately) living well, without rancor," Nelson said.

So began Khamkeo's seven years, three months and four days as a political prisoner. He said he wore handcuffs for 18 straight months. He was forbidden to communicate with his family and didn't know that his wife had bribed officials to send him letters and provisions. None ever arrived.

"I knew my wife and our four children loved me and waited for my release," Khamkeo said. "To deserve their love, I told myself to be strong, to endure and to return home."

Eventually, the political climate shifted, and Khamkeo was freed. He and his family fled Laos for Thailand six months later. They emigrated to the United States, settling in Tennessee and Maryland, before arriving in Vancouver in 1992. Of their four children, now all adults, only the youngest still lives at home.

Khamkeo said he chose Vancouver because a friend of a friend mentioned the Portland area might offer a variety of employment prospects. Starting over in his mid-40s was the most difficult adjustment for Khamkeo, who speaks three Chinese dialects and five other languages. Between the restaurant and his addiction counseling at OHSU, the family is scraping by. Khamkeo said OHSU hired him to work with Asian clients who have alcohol, drug and gaming problems. But few Asians are willing to seek help, because most have been raised not to speak of such issues, Khamkeo said.

Khamkeo said his book is the first to be written about human rights violations in Laos, by a Laotian in English, and published in the United States. Nelson said he believes that's true.

Although Khamkeo naturally hopes the book will sell well, he says he wrote it from a burning need to tell the truth about human rights violations in his homeland. His survival depended on his belief that he would be able to do so.

Did you know?

"I Little Slave" was a formal style of address in prerevolutionary Laos, used in place of the word "I," to address an elder or person of higher social standing. The communists scrapped the phrase as an insult to members of a classless society, but then forced political prisoners to use the term as a form of humiliation.

The Pathet Lao began as a communist movement in Laos in the mid-20th century. After communist forces prevailed in Vietnam and Cambodia, the Laotian coalition government collapsed, and the Pathet Lao took power in Laos in 1975. The country is known today as the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

look for it on amazon.com (to be released in february...)

2 comments:

thank you - i'd like to read that.

i like that you're on holiday and can blog so much. too bad i was on holiday and reading much of it late.

yeah, i think i am gonna go hear him speak... its amazing cause nobody has ever written a book about Laos in this way; seen them on cambodia, vietnam, and even the hmong of Laos - but nothing by Lao people...

so its overdue....

Post a Comment